Tags

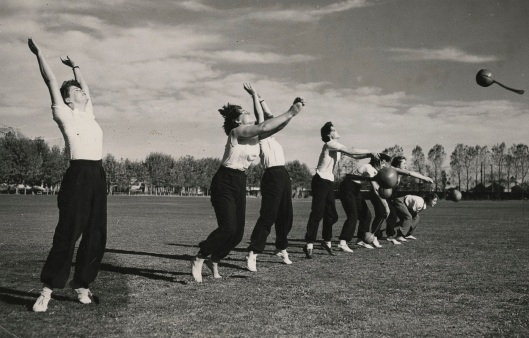

Taken from the Aquinas building site in the 1950s, this photograph shows part of its fabulous view over campus and city. Image courtesy of Aquinas College.

Aquinas College is yet another part of the university which marks a milestone this year: it opened 60 years ago, in 1954. It hasn’t been open for 60 continuous years, though; strictly speaking, this is its 54th year as a residential college. In 1948, with a surge in student numbers in the wake of World War II, there was a growing need for student accommodation. The Catholic Bishop of Dunedin, James Whyte, wrote to the Dominican Order in Australia, asking if they might do something about “the crying need in Dunedin of a hostel for the Catholic students who come here to the Medical School.” The Dominican Sisters had opened Dominican Hall, which catered for women students, in 1946, but there was no similar facility for men. The churches were heavily involved in providing accommodation for Otago students. The Anglicans built Selwyn College (opened 1893) and the Presbyterians Knox (1909) and St Margaret’s (1911). Their founders wanted to promote education, meet an obvious community need, and provide pastoral care to their young people. Though the colleges were open to students of all denominations and none, the Catholic Church naturally hoped to provide a facility which would keep its student members under its own wing.

In response to the Bishop’s request, in 1949 Fathers Leo McArdle and Denis Crowley arrived in Dunedin to take over Sacred Heart Parish in North East Valley and begin planning the new college. The Dominican Sisters, who had been providing Catholic education in Dunedin since 1871, donated land adjacent to their Santa Sabina Convent for the new project. Located at the top of a steep hill, it had expansive views over the city and directly across North East Valley to Knox College (Knox and Aquinas residents sometimes howled at one another across the valley and became natural rivals in student hijinks). The Dominican Fathers raised funds through public subscriptions, a bank loan and a government subsidy, and building commenced in 1951. The design was an early project of renowned Dunedin architect Ted McCoy; it won him the New Zealand Institute of Architect’s gold medal.

In 1954 the first residents moved into Aquinas Hall, named in honour of the great medieval theologian St Thomas Aquinas, the most famed of Dominican friars. The 72 pioneering residents – all men – included many medical and dental students, but also a variety of others, including physical education and teachers’ college students; about two-thirds were Catholic. Fathers Bernard Curran and Ambrose Loughnan and Brothers Martin Keogh and Peter O’Hearn joined Father McArdle to form the college’s first Dominican community; the death of founder McArdle late in 1954 was a great loss to Aquinas. In keeping with the scholarly goals of the college, and of the Dominican order, the residents had a large library and tutorial rooms as well as their common rooms and chapel. Early residents hold fond memories of the friars and of life at Aquinas; they quickly developed into a close community and indulged in all the usual student activities and pranks (including stealing all of Knox’s cutlery).

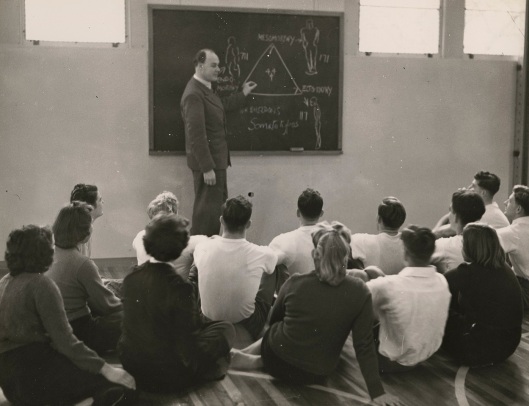

The 1966 residents of Second Floor North pose for the Aquinas magazine, ‘Veritas’. Image courtesy of Aquinas College.

Aquinas flourished through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, but in 1980 it was in trouble. The problem was not peculiar to Aquinas; that year the Vice-Chancellor reported about 100 vacancies in Otago residential colleges. The university roll had increased a little, but would actually decline in 1981 and further in 1982; to aggravate the situation in Dunedin, an increasing number of students were now based at the Christchurch and Wellington clinical schools, and the teachers’ college intake had dropped. The days when many students stayed in a college for their entire degree had gone, and more and more were now going flatting after a year or two. There was simply less demand for college accommodation. The Dominican Sisters stopped offering student residence at Dominican Hall in 1978; at the end of 1980 the Dominican Friars closed Aquinas with much regret, as they could not afford to keep it open. They sold the building to the Elim Church and part became a backpackers’ hostel for some years.

By the mid-1980s the University of Otago roll had begun to rise again, and from the late 1980s it boomed. The university was desperate to find accommodation for first year students. In 1984 it opened a ‘temporary’ residential college – Helensburgh House – in the Wakari Hospital nurses’ home (it was to survive until the university instead secured in 1992 the former maternity hospital which became Hayward College). The former Aquinas Hall – purpose-built as a residential college – was clearly ideal for the university’s purposes and it managed to purchase the building from Elim Church and open it under a new name – Dalmore House – in 1988. Seventy-three brave students and warden Reywa Clough moved into the run-down facilities, which were slowly upgraded. At the end of the year the university managed to secure the lease of the neighbouring former Santa Sabina Convent, which became an extension of Dalmore and home to a further twenty or so residents. Today the expanded and much improved facilities are home to 165 residents. The former chapel is now a gymnasium, but the Catholic heritage of the college was marked in 1996 when, with the permission of the Dominicans, it was renamed Aquinas.

Do you have any memories to share of Aquinas/Dalmore/Aquinas?