J.W. Allen took this photograph in the late 1860s from around where Marama Hall is today, on what was known as Tanna Hill. On the right in the middle distance is a circular garden, part of the original Botanic Garden on Albany St. On the left is the Cook family home (now Mellor House). The Leith, which is not visible, wound around the bottom of the hill. The university moved to this site in the late 1870s. Parts of Tanna Hill were levelled for building, notably the land where the Archway Theatres and Applied Sciences Building are now. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Album 68, S14-434b.

I’ve been on an intriguing mission to identify the oldest surviving building on the Dunedin campus. Assisting me were two architectural history experts – David Murray (Hocken Collections), keeper of the wonderful Built in Dunedin blog, and Michael Findlay (Department of Applied Sciences), who sparked the idea for this project and then helped me identify likely suspects. I’m most grateful to them, and also to Chris Scott of the city council archives, who helped with clues in old rates records.

When considering old University of Otago buildings, most people probably think first of the old stone buildings at the centre of the campus. When the university council decided to move operations from the original location in Princes Street, it commissioned two large buildings on its new site beside the Leith in North Dunedin. Work on the chemistry and anatomy building (now the geology building) was completed in 1878, and on the main building (now the registry) in 1879. Both were smaller than they are today, with extensions added in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. The St David Street homes for four professors (now known as Scott/Shand House and Black/Sale House) were also completed in 1879.

As the university expanded, it began acquiring properties neighbouring its original block of land. Often these included old houses, which ranged from tiny cottages to substantial residences. Some were later demolished to make way for new buildings but others have survived, including a few which pre-date the geology building. Their original residents had no idea they would one day be living close to a university, let alone that their house would one day be part of it!

We are pretty certain that the honour of being the oldest building on campus belongs to Mellor House, one of the old Union Street houses now occupied by the psychology department. The house was originally built in 1862 for Thomas Calcutt, a printer who migrated from England to Otago in 1858. As well as continuing to work in the printing trade, Calcutt served as a court clerk and later became a valuer of land taken for public works. He probably picked up the latter job because of his experience as a land speculator, for his 1895 obituary notes that “he displayed much natural shrewdness in matters of business, and made many profitable speculations in landed property.” Early on – certainly by 1861 – he acquired all of the land in the block bounded by Clyde Street, Union Street, Leith Street and the river; there were no houses on the land at that stage. In March 1862 advertisements appeared in the Otago Daily Times for carpenters and painters for “a Dwelling House now building for Mr Thomas Calcutt, Pelichet Bay. Apply to the foreman on the Ground.” By October of that year, Thomas and Mary Calcutt were living in their new home, dubbed Leith Cottage, where Mary gave birth to their son Arthur.

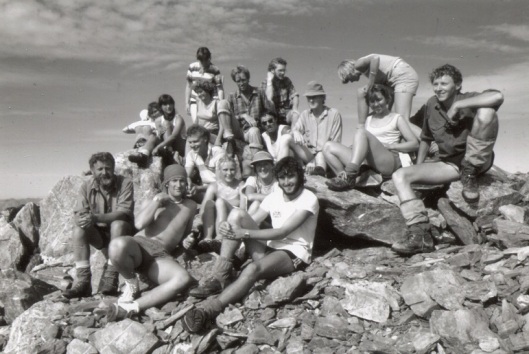

Sadly, baby Arthur Calcutt died at just four months, but in January 1864 another child was born at Leith Cottage, this time to its new owners, George and Ann Cook. While the Calcutts’ stay in the house had been brief, the Cook family were to own it for eight decades. George Cook was an English solicitor who arrived in Otago late in 1860 and was admitted to the New Zealand bar in January 1861; intriguingly, his wife Ann and one of their children migrated a couple of years earlier, on the same ship as Thomas Calcutt. The final reference I have found to the name “Leith Cottage” dates from 1868, when Ann Cook advertised for a general servant. Perhaps this name was dropped as the house was extended: like many houses of the period it has clearly been enlarged from humbler beginnings.

The house at 93 Union Place, which dates from the early 20th century, was moved there from the site of the new Commerce Building. Photographed by Ali Clarke, August 2014.

By the time George Cook died in 1898, aged 82, he was Dunedin’s longest serving lawyer. He was a careful and conservative practitioner: “an upright, estimable lawyer of the old English school – a man who brought with him to the colony all the traditions and all the prejudices of the English bar, and who resented all innovations.” The Cooks lived in splendid isolation on their property until around 1902, when further houses were added to the block; presumably Ann Cook sold off some of the land after her husband died. Some of the houses built around that time also survive and are now occupied by the psychology department, including those at 99 Union Street (next to the Commerce Building) and 97 Union Street (Galton House). The charming two-storey house on the corner of Leith and Union streets was originally at 103 Union Street, but moved to its current location at the top of the hill in 1990 to make way for the new Commerce Building.

Galton House was built in the grounds of the Cook family home in the early years of the 20th century. Photographed by Ali Clarke, August 2014.

When Ann Cook died in 1907 she left the original family home to son John Alfred Cook. John Cook was another solicitor; indeed he practised together with his father for some time. Law ran in the family: another son, Reginald Cook, was a lawyer in Sydney, while daughter Clara Cook married lawyer Frederick Chapman, who became a well-known judge. Their brother George was a government engineer, while Spencer was a banker and Montague worked for Dalgetys. Later Cook generations also entered the law, and the name survives as part of legal firm Gallaway Cook Allan. John Cook died at his Union Street home in February 1945 at the ripe old age of 92 years and his wife Margaret died four months later.

At that time the university was on the lookout for houses suitable for student accommodation. The roll was on the rise, and would shoot up in 1946 as returned servicemen came to university. It purchased the Cook family home and named it Mellor House in honour of one of Otago’s most successful graduates, chemist Joseph Mellor. A blueprint drawn up for the university in 1945 reveals it as a substantial residence, with six bedrooms, a study and a bathroom upstairs. Downstairs were a drawing room, dining room, library, kitchen, scullery, pantry and bathroom, and there were a couple of outbuildings as well.

The growing university needed room for classrooms and offices as well as student bedrooms, and in 1946 Mellor House began its life as a university building with a dual purpose. Upstairs the bedrooms became an outlying part of Arana Hall. The “Mellor House boys” – a mixture of returned servicemen and young school leavers – had their meals at the main college but slept in the old Cook family bedrooms. Arana still has a delightful photograph of one of the residents dressed in some old Victorian woman’s clothing they discovered upstairs! Downstairs became the home of the newly established Department of Geography. Two rooms were knocked together to create a classroom and the pantry became a staff office. Tea on the verandah was a departmental tradition.

The mixed use of the building could be interesting at times. Saturday morning geography labs were often accompanied by the “Mellor House boys” singing in the shower, and fuses frequently blew due to residents plugging toasters into light sockets. As the geography department grew, it gradually expanded upstairs and into a prefab hut in the garden; the last Arana “boys” lived at Mellor House in the late 1950s. Late in 1964 geography moved to the newly built Library/Arts Building (since replaced with the ISB Building). Mellor House then became home, once again, to a newly established department: this time it was psychology.

The Department of Psychology now has a claim to one of the university’s most modern large buildings – the William James Building, completed in 2010 – and what is almost certainly its oldest building – Mellor House, completed in 1862. I wonder what colonial property developer Thomas Calcutt and the legal Cook family would think of the current use of their home!