The crèche in its original premises in the old All Saints Church Hall. The notes on the back of this photo are difficult to decipher. The voluntary helpers are identified as Vivienne Moss (although that name is crossed out) and Jenny Heath. The child facing the camera at the centre is Rebecca, with Rachael nearest the camera. Please get in touch if you can confirm any names! Photo courtesy of the Otago University Childcare Association.

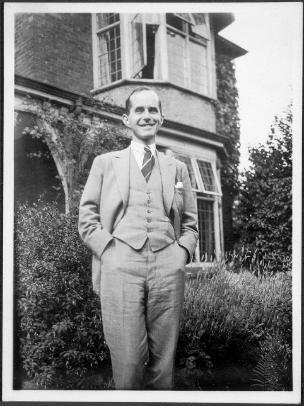

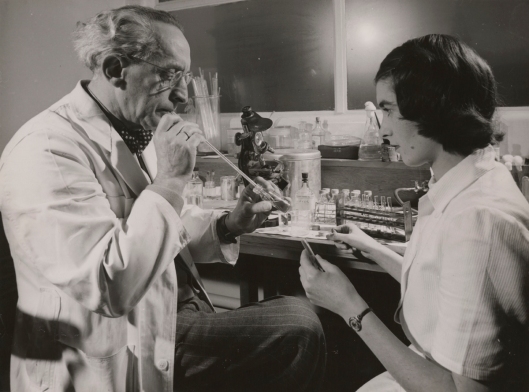

There is one organisation affiliated to the university which, although unknown to some students and staff, has had a big impact on the institution since it began nearly 50 years ago: the Otago University Childcare Association (OUCA). During the university’s first century there were few women academics, even fewer married women academics and scarcely any with young children. Microbiologists Margaret and John Loutit arrived at Otago from Australia in 1956; Margaret obtained part-time work as a botany demonstrator and then microbiology lecturer while working on a PhD. As a working mother she encountered considerable criticism. Her salary was mostly absorbed in paying for private childcare, but her hard work was rewarded with the completion of her PhD in 1966; she then became a full-time academic and eventually a professor. For many others, motherhood spelled the end of any academic career, while most students abandoned degrees when they gave birth. In the 1960s and 1970s, when many New Zealanders married young and, whether married or not, also had children young, that meant a lot of ‘academic wastage’.

Improving childcare provision helped the next generation of women. Several younger staff wives instigated the university’s first crèche, designed to provide part-time childcare for students. Since the university was unwilling to provide childcare, the founders set it up as a community venture; the vicar of All Saints Anglican Church offered the use of the old church hall. They invited women students to a meeting late in 1968 and ‘it was evident from the animated discussion that a nursery would fulfil a need’. The University Nursery Association – later renamed the Childcare Association – was a parent cooperative, with Jean Dodd as first president; she was a lecturer’s wife who previously set up a playcentre in Leith Valley. The nursery/crèche (both names were used at various times) opened in 1969 with kindergarten teacher Barbara Horn and Karitane nurse Ann Leary as its first supervisors; parents provided assistance according to a roster.

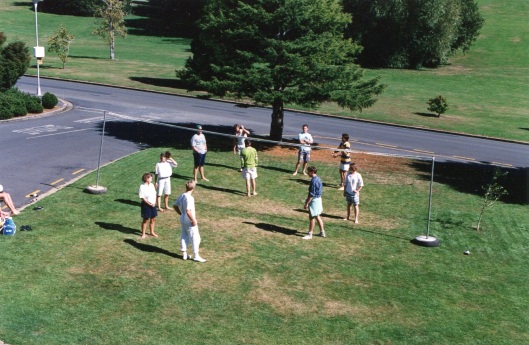

Outdoor play and learning in the 1990s. Photo courtesy of the Otago University Childcare Association

The new affordable and convenient crèche, together with new access to contraception, made a big difference to women, comments one student of that era, Rosemarie Smith: ‘gaining control over fertility and creating childcare revolutionised women’s access to education – and also to employment in the university’. She ‘graduated in 1971 with a BA and a baby thanks to that crèche’, and worked on the general staff for a couple of years. There was some resistance to the crèche. Most people in positions of authority in the university – generally men – saw no need for it, but there was also resistance from women uneasy about working mothers. There was, however, a demand for childcare and the association grew quickly, from 39 paying members in 1969 to 83 in 1971. That year it moved into the Cumberland Suite (an old house) of the University Union and in 1973 into a house at 525 Great King Street. That was provided by the university as temporary accommodation, since it intended to demolish the building to make way for a carpark. Instead it became a long-term home for the association, which expanded into two adjoining houses in the 1980s.

Childcare became more respectable as increasing numbers of middle-class married women joined the workforce. OUCA helped overcome some resistance in its early years by insisting it was a part-time service, but from 1980 it offered full day care. The service was increasingly used by staff, although students retained priority. In 1994 there were 138 families using university childcare; 71 were staff and 55 were students. It remained affiliated to, rather than owned by, the university, although the university provided its buildings – including splendid new Castle Street premises in 2014 – and small grants from the university and students’ association covered a small portion of its expenses. Unsurprisingly, given its clientele, OUCA attracted highly capable people to its management committee. Among the parents who served were some who subsequently held senior posts in the university, including future vice-chancellor Harlene Hayne; she was succeeded as president by historian Barbara Brookes, who suggests it ‘was perhaps the most important committee in the university in terms of the connections we made’. Brookes, her husband (also an academic) and children all made, through childcare, ‘deep friendships that nourish us today’.

Behind the facades of several villas in Castle Street, across the road from Selwyn College, Te Pā opened in 2014 as new premises for the Otago University Childcare Association. It incorporated four childcare centres, including a new bilingual centre, Te Pārekereke o Te Kī. The association also continued to run a centre at the College of Education. Graham Warman photographs, courtesy of University of Otago Marketing and Communications.