Tags

1870s, 1880s, 1890s, 1900s, 1920s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, chemistry, medicine, pharmacology, pharmacy, physiology, toxicology, Wellington

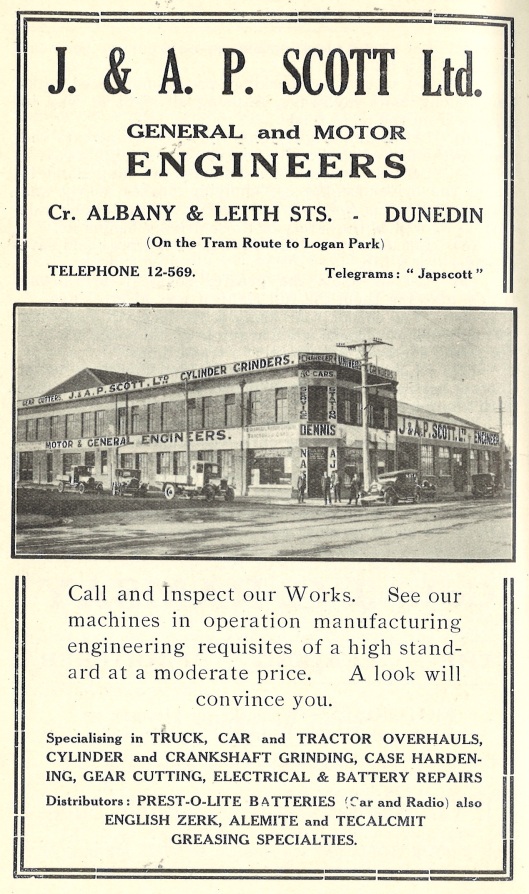

Making up supplies of the new wonder drug, penicillin, in the pathology department’s sterile solutions unit in 1949. In the 1960s the new pharmacy school took over ‘the factory’. Please get in touch if you can identify the woman in this photo! Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Prime Minister’s Department photograph, Box-184-007, S16-102a.

The University of Otago’s interest in pills and potions and poisons dates back to its earliest years. In his first annual report on the university laboratory, in 1875, chemistry professor James Black listed all the analyses he had carried out for the public and local officials. They ranged widely, from food and drink he tested for adulteration to coal and minerals and cement he tested for quality. Also on the list were some samples which suggest intriguing mysteries: in June 1874 Dr Niven of Roxburgh sent medicine, pills, a piece of tart and some lung balsam for testing, while in October Dr Cole of Tokomairiro sent urine and other samples to be tested for poison. Toxicology was thus at the very origin of Otago’s work in the pharmacology field.

It was the establishment of the medical school, though, which led to the first employment of a specialist in drugs. In 1883 John Macdonald was appointed lecturer in materia medica, as pharmacology was then known. The first medical school historian, Dudley Carmalt Jones, described Macdonald as ‘a big, handsome Scotsman of a striking presence …. a man who never quarrelled, and never did anything unethical’. As well as teaching students about drugs, he gave clinical teaching as one of the Dunedin Hospital honorary staff, his specialty being skin diseases. Macdonald taught materia medica according to ‘Edinburgh tradition’, with long lists of drug preparations to be memorised. Students also learned the practical skills of pharmacy, including the visual recognition of drugs and the making of pills, ointments and potions. These skills were taught at the hospital by its dispenser. The first to teach medical students their pharmacy skills was Dr John Brown, ‘a dear old eccentric teacher’ who was hospital dispenser for many years. This well-known character was apparently quite lenient with the students, but his successor refused to sign them off as ‘fully competent’, only recording that they had ‘regularly attended’; he also suggested that ‘grave danger’ could be avoided if they learned the theory of materia medica before tackling the making of medicines.

Although the early pharmacology lecturers focused on teaching rather than research, there were some interesting studies taking place around the university. As I wrote in an earlier post on this blog, New Zealand’s first home-grown medical graduate, Ledingham Christie, was awarded an MD degree in 1890 for his research into the toxicity of the tutu plant. In time-honoured mad scientist fashion, after observing the effects of the tutu berry on cats, roosters and rabbits he tested it on himself, taking a month to fully recover! Otago’s first physiology professor, John Malcolm, began working on tutin soon after his 1905 arrival, together with research assistant and hospital physician Frank Fitchett. Their authoritative study On the Physiological Action of Tutin was published in 1909. The following year Fitchett – a local lad who had returned to Dunedin after completing the final years of his medical training in Edinburgh – became pharmacology lecturer. Medical students enjoyed his lectures, even though they took place at 8am, for he filled them with a great fund of entertaining anecdotes from his years of medical practice. In 1920 Fitchett was promoted to be part-time professor of clinical medicine and therapeutics. He visited medical schools in England and Scotland to check out their pharmacology programmes; Otago needed to adapt its teaching to meet the changing requirements of the General Medical Council. Practice in hospital dispensing – ‘condemned’ as unnecessary by the council – was dropped from Otago’s medical syllabus and replaced with a practical class, modelled on Edinburgh’s, in the writing and analysing of prescriptions, and observation of the effects of drugs.

In 1940, after Fitchett retired, Otago had the good fortune to recruit the brilliant Horace Smirk to a new full-time professorial post in medicine. He was a Manchester graduate who worked in London and Vienna before becoming pharmacology professor in Cairo; he continued his pioneering work on drug treatment for high blood pressure in Dunedin. The new professor started out with a boosted staff of lecturers and researchers and within a few years had added further to his team. It was largely in honour of Smirk’s work that Otago received a large grant from the Wellcome Trust in 1961 for a new research building. Smirk had ‘tremendous vitality’, recalls Fred Fastier, one of his pharmacology team (later a professor himself). His colleagues wondered if this had something to do with the enormous quantities of tea he consumed; was his ‘curiously strong brew’ converted into something special ‘by a process apparently acquired in the land of Egypt’? It didn’t, however, work the same way for them.

Meanwhile, the Medical Research Council set up a toxicology research unit at Otago in 1955. Frank Denz was recruited back from England to his home country as first director; with a team including chemist Jack Dacre he began work on food additives such as colouring agents, ‘chosen because they were in extensive use but had not had adequate toxicological assessment’. Denz also taught in the pathology department; after his death in 1960 a very small team carried on with toxicology research. In 1968 the MRC convinced Garth McQueen of the pharmacology department to become director of the unit; he was an Australian who came to Otago in 1954 to work on hypertension with Horace Smirk and stayed on as lecturer in clinical pharmacology. In 1964 McQueen established the New Zealand National Poisons Information Centre, inspired by Dacre’s observations during study leave in the United States. It started out as a one-man operation, run from the Dunedin Hospital Emergency Department, and grew into a busy standalone 24/7 public service with an enormous knowledge base; alongside it McQueen developed New Zealand’s Centre for Adverse Drug Reactions and the Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme (IMMP). Developed in the wake of the thalidomide tragedy, these, too, provided important public services, recognised with dedicated government funding from 1982 (the IMMP closed in 2013 after losing funding).

Another important 1960s development started out in a very small way: in 1963 six students signed on for a new Otago pharmacy degree. Pharmacists had been pushing for higher education for decades. New Zealand had been registering pharmacists since 1881, requiring them to complete an apprenticeship and pass exams; various private colleges developed. In 1960 the profession finally succeeded in getting a new pharmacy diploma course underway at the Central Institute of Technology (CIT); the Otago degree course was intended for those destined for specialist positions as researchers, lecturers, hospital pharmacists or manufacturing pharmacists. Pharmacy academics were thin on the ground, so the vice-chancellor persuaded pharmacologist and ‘born optimist’ Fred Fastier to administer the new course. Two highly regarded local pharmacists – analytical and consulting chemist Roy Gardner and Dunedin Hospital chief pharmacist John Conroy – ‘came to the rescue’ and became part-time lecturers for the specialist pharmacy subjects. The old Dental School Annexe (next to what is now the Marples Building) was converted to provide specialised labs for the pharmacy programme and sterile solutions unit, which pharmacy took over from the pathology department. The sterile unit – better known as ‘the factory’ – had been manufacturing supplies, including solutions of penicillin and other drugs, for many years to sell around the country; the pathology professor had kept it going in the hope it would prove useful for a future pharmacy department.

Pharmacy student Alan McClintock and technician Sandra Barkman identifying ‘unknown’ chemical compounds in Rob McKeown’s pharmaceutical chemistry lab, c.1983. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections, University of Otago Photographic Unit records, MS-4368/085, S16-669c.

There was plenty of demand for Otago pharmacy graduates and lots of interest in the course; the annual intake was quickly increased to 20 and in 1975 to 25. In 1971 Harry Taylor, who had been heading the CIT programme, became Otago’s first pharmacy professor. A 1981 retirement tribute noted that Taylor saw pharmacy flourish ‘in the most decrepit building in the university, with his administrative work performed in an office no bigger than a commodious cupboard’, but in 1985 it finally moved into better accommodation in the renovated Adams Building. The pharmacy programme was also renovated under energetic Canadian professor Donald Perrier, who introduced a more clinical focus to the degree, which was popular with students. The class continued to grow, taking its biggest jump in 1991; that year, following a long period of political wrangling, a degree became the minimum standard of entry to the pharmacy profession, the CIT course closed and all New Zealand pharmacy training shifted to Otago (from 1999 pharmacists could also qualify through the University of Auckland). The pharmacy department was upgraded to become the pharmacy school, with Peter Coville – affectionately known as Papa Smurf – as first dean.

While pharmacy developed its own postgraduate programmes and research, staff in pharmacology, psychology and several medical school clinical departments also continued a wide variety of research concerning pills and potions and poisons. Some of these had big consequences. In the 1970s McQueen and Otago paediatricians were among those who revealed the toxicity of popular antiseptic hexachlorophene on premature babies. It was widely used from the 1950s onwards in the fight against staph outbreaks in maternity hospitals, but carried its own dangers. Perhaps the most dramatic finding concerning prescribed drugs came through a group of young researchers at the Wellington campus in the late 1980s. Physicians Julian Crane and Richard Beasley and pharmacologist Carl Burgess, all from the medicine department, were suspicious that a popular asthma drug, fenoterol (marketed here as Berotec), might be contributing to an unexplained epidemic of asthma deaths. They asked epidemiologist Neil Pearce of the Wellington campus’s public health department to join them in a study. The results, published in the Lancet in 1989, were explosive, revealing an association between asthma deaths and fenoterol. As with many epidemiological studies, the findings proved controversial. The drug manufacturer, Boehringer Ingelheim, conducted a remarkable campaign to discredit the study, but they weren’t the only ones to dispute it: other researchers, including some of Otago’s own, also resisted suggestions that fenoterol was dangerous. Further studies confirmed the asthma research group’s findings and government subsidies for fenoterol were withdrawn; it was research which prevented many asthma deaths in New Zealand and around the world. From investigating suspicious lung balsams in the 1870s to uncovering dangerous asthma inhalers in the 1980s, we have many reasons to be grateful to Otago researchers.