Tags

1940s, chemistry, clothing, home science, human nutrition, medicine, physics, Studholme, war, women

A tarpaulin lean-to operating theatre of the 6 New Zealand Field Ambulance near Cassino, Italy. Many Otago medical graduates found themselves working in facilities like this during World War II. Photographed by George Robert Bull on 25 April 1944. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Department of Internal Affairs War History Branch collection, DA-05591-F.

In the midst of all the centenary commemorations of World War I, the 75th anniversary of World War II has been rather overshadowed. As I’ve written here before about the impact of World War I on the University of Otago, I’m marking Anzac Day this year by considering the university’s involvement in the second great conflict of the 20th century.

As had been the case during the ‘Great War’, many Otago staff and students served with the forces during World War II and the conflict had an enormous effect on those people and their families and friends. The exact numbers involved are unclear, but the university annual report for 1942 gives figures for that stage of the war – as of December 1942, 13 members of staff and about 725 students and former students were on active service, and 28 had died. Since the total student roll of the university just before the war was around 1400, this was a very significant contribution. Many other students spent their vacations completing military training. For medical and dental students, this was done through the Otago University Medical Corps. Some students not involved in military training were instead manpowered to carry out essential work on farms during breaks.

Student enrolments dropped off during the first half of the war, hitting a low of 1348 in 1942 before steadily rising again to 1839 in 1945; the end of the war led to a big influx of students in 1946, when the roll reached 2440. Variation was huge between the different faculties. There was a significant wartime drop in the number of arts students, but it was the small commerce and law faculties which fared the worst. Meanwhile, science and home science numbers increased, and those in medicine flourished as the demand for doctors both military and civilian grew. The medical school struggled to resource this student growth and had to introduce restrictions on entry to second-year medical classes for the first time in 1941. One unfortunate result of such restrictions was public resentment towards war refugee doctors (mostly Jews from Germany, Austria, Hungary and Poland) who had been accepted into New Zealand. Some were required to complete further training at the medical school – they were seen to be taking places ahead of New Zealand students. The attitudes of both medical school and university towards these refugees were decidedly mixed.

In 1942 the medical school accounted for 40% of Otago students, a percentage only reached once previously, and that was during World War I. Med students were a traditionally conservative group and their dominance contributed to what OUSA historian Sam Elworthy has described as “the death of political radicalism” on campus during the war. Of course, other wartime influences played their part. Students wanted to demonstrate their loyalty in an environment of public suspicion, where citizens believed healthy young men who continued at university were shirking their patriotic duty. Wartime did offer new leadership opportunities for women, who increased from around 25% of students in the mid-1930s to 40% in 1942 (a percentage they would not reach again until 1976, after dropping back below 30% after the war). Women were elected to the students’ association executive, edited Critic and became presidents of the dramatic and literary societies.

Otago’s Professor of Chemistry, Frederick Soper, co-ordinated New Zealand’s war efforts in chemistry. He is photographed around December 1946. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, New Zealand Free Lance collection, PAColl-8602-66.

As well as supplying numerous personnel to the military forces, the University of Otago made important contributions to the war effort through its scientific work. Government scientists and the universities cooperated on various projects. At Otago, Professor Robert Jack and his colleagues in the physics department worked on infrared sensors for the detection of shipping. Frederick Soper, the chemistry professor (later vice-chancellor), chaired the chemical section of the national Defence Science Committee, whose projects mostly related to producing products in short supply due to the war, including munitions and many other items which were normally imported. Otago staff worked on an antidote for war gas, production of chemicals required for naval sonar and smoke bombs, and the testing of New Zealand ergot (an essential drug used in obstetrics). Stanley Slater of the chemistry department produced morphine using opium which had been confiscated by the police under drug legislation (the same project was carried out during World War I by Prof Thomas Easterfield at Victoria University of Wellington).

War and post-war food shortages also inspired various university projects. Leading Otago scientist Muriel Bell was appointed government nutrition officer, setting the food ration scales and continuing her applied research into New Zealand foods. Among many other things, she was well-known by the public for her rosehip syrup recipe, designed to supply Vitamin C to young children. The School of Home Science got involved in the war effort right from the beginning, using Studholme Hall to train local women in large quantity cookery, so they would be prepared in case of emergencies in hospitals. The school’s clothing and textile experts advised on the manufacture of garments for soldiers.

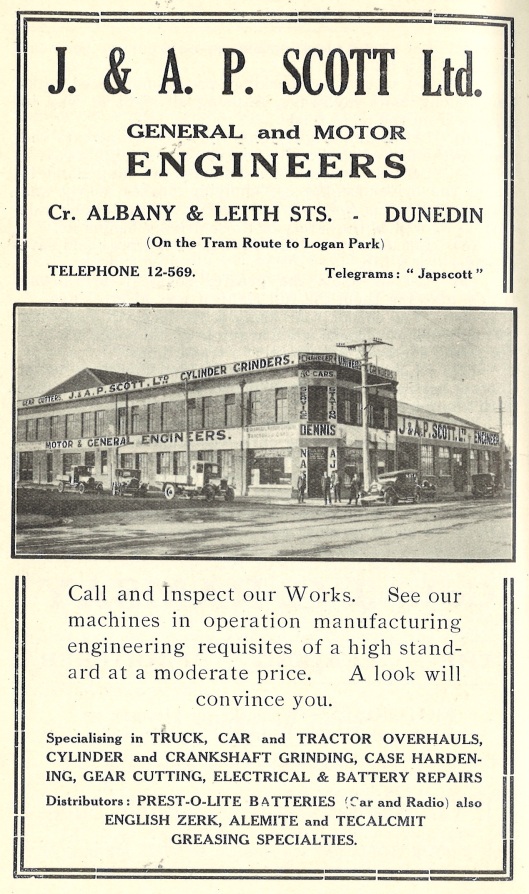

I haven’t found any references to deadly weapons being produced on campus, but one of the university’s neighbours became a munitions factory during the war. Engineering firm J & AP Scott, located on the corner of Leith and Albany streets, produced 3-inch mortar shells and cast iron practice bombs, with the government doubling the size of their building to aid this war work. The university later took over the Scott building, which has been the home of Property Services for many years.

A 1920s advertisement for engineering firm J & AP Scott, which manufactured munitions during World War II. The university later took over the building. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections, from the Otago Motor Club Yearbook 1927-8, Automobile Association Otago records, 95-056 Box 97.

In the 1970s, looking back on World War II, Frederick Soper commented that it was “popular to accuse the Universities of being ivory towers but I should like to affirm that University policies do respond to national needs.” The research efforts of New Zealand universities during the war led to growing support for their research in the post-war period. One very significant result was the re-introduction of the PhD degree in 1946 – it had first been offered in the wake of World War I but withdrawn after just a few years. For better and for worse, the war of 1939-1945 clearly had a major impact on Otago. Do you know of any other stories relating to the university and the war?

Hullo Ali, I read you are into history. I have just finished a book “A Dame. We. Knew”

A tribute to Dame Cecily Pickerill wife of Dr henry p Pickerill 1st dean of the dental school. She was our first medical Dame and a pioneer in her own right, of infants plastic surgery, mainly clefts, and the infants being nursed thru surgery by their own mothers. I would like for you to have a copy if you send me a postal address.

Regards. Beryl. Harris 8 a. Murray street upperhutt.

Hi Beryl. I’ve heard of Dame Cecily – what a remarkable pair they were! There’s a copy of your book at the Hocken, which I can easily consult. Great to see this tribute to her. But if you have a copy to spare that would be nice – thanks so much. My postal address is c/o the Department of History, University of Otago, PO Box 56. Best wishes, Ali

Pingback: Eight vice-chancellors | University of Otago 1869-2019

Pingback: On a foreign field | University of Otago 1869-2019

Pingback: “Great Britain needs ergot from New Zealand” | Spores, moulds, and fungi