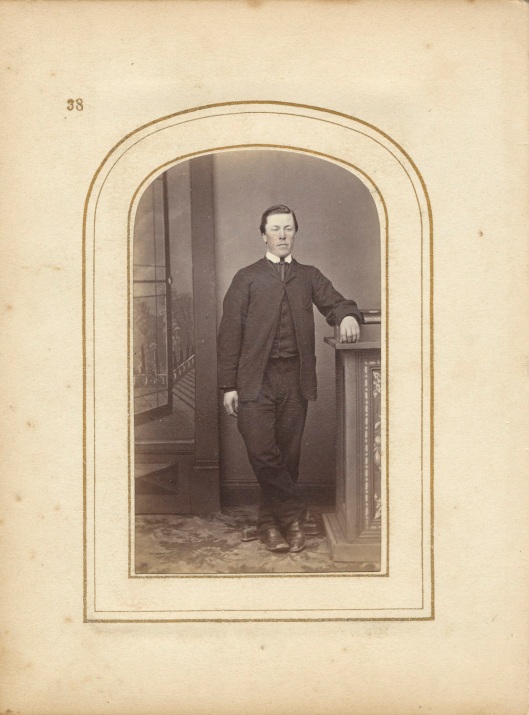

Robert Stout, future Premier of New Zealand, claimed the honour of being the University of Otago’s first student. This photograph was taken four years later, in 1875, by the NZ Photographic Co., Dunedin. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Box-030-001, S10-021a.

When classes commenced at the University of Otago in July 1871, the first student to sign on was a 26-year-old lawyer named Robert Stout, admitted to the bar just a few days previously. Though nobody knew it at the time, Otago’s first student was an omen of a good future: Stout became Premier of New Zealand and later Chief Justice. He arrived in Dunedin from his native Shetland in 1864 with teaching experience and surveying qualifications in hand; after a few years teaching he commenced legal training. The energetic Stout was well known around town for he was involved in numerous organisations and notorious as a leading freethinker, who loved debating against religious orthodoxies. His student career was not a long one and he did not complete a degree, but it had important consequences, for he was greatly influenced by the mental science professor, Duncan MacGregor, and later recruited him to become one of the country’s top public servants. Stout’s political career began in 1872, when he was elected to the Otago Provincial Council, but he still found time to serve as the university’s first law lecturer from 1873 until 1875, when election to parliament spelled the end of any academic career. However, his influence on New Zealand universities was immense. He was a member of Otago’s university council for several years and later that of Victoria College (now Victoria University of Wellington), of which he was ‘principal founder’; he also served on the senate of the University of New Zealand for 46 years and was its chancellor from 1903 to 1923.

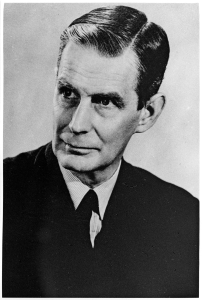

Peter Seton Hay, the brilliant young mathematician who was one of New Zealand’s earliest graduates. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, P2010-011/1-024, Album 605, Hay family portraits, S16-683a.

The university attracted 81 students to its first session. Few student records survive – those identified from various sources are listed at the bottom of this post. Only 20 successfully passed their exams. The others presumably failed or abandoned their studies: ‘not a few dropped attendance, finding the task of preparation too burdensome’, noted council member Donald Stuart. Many, like Stout, were full-time workers and part-time students. Others may have had more time to devote to their studies, but found themselves ill-prepared for tertiary-level education; some did not have the privilege of a high school education. When the Evening Star in 1878 referred to maths and physics professor John Shand as ‘the lucky tenant of one of the University sinecures’, former student Gustav Hirsch rushed to his defence, noting Shand’s heavy workload and the success of his teaching: ‘One of his first students was taken from an elementary school at a very small place up-country, and had just managed to pick up a little mathematical knowledge from the mathematical volume of the “Circle of the Sciences”. Under Professor Shand’s guidance this student a few years afterwards graduated a first-class, with honors in mathematics, and is now an M.A.’ That student was Peter Seton Hay, who had migrated from Scotland as a child and grown up on the family farm at Kaihiku, in the Clutha district; he subsequently became a noted engineer, known particularly for the railway viaducts he designed. He was also famous for ‘prodigious mental calculations’ and ‘solved abstruse mathematical problems in his leisure hours’.

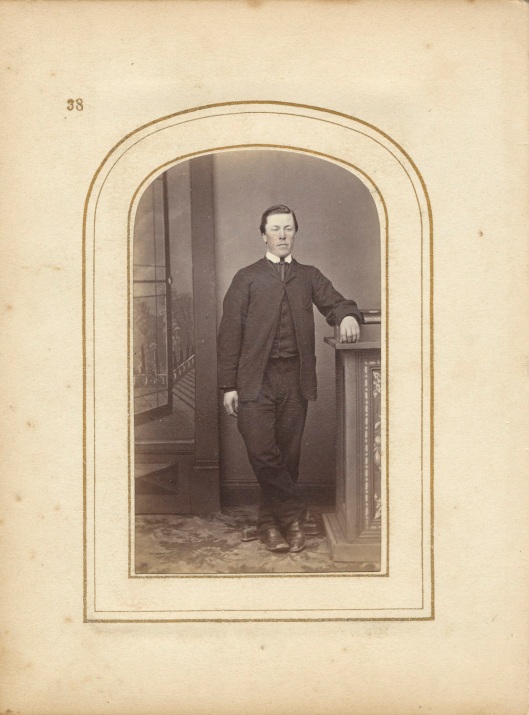

Hay was one of the few early students to complete a degree; most attended classes for a year or two, or even longer, but did not graduate. Otago’s first degree, a BA, was awarded to Alexander Watt Williamson in 1874; it then put aside its power to award degrees in favour of the University of New Zealand, which remained the country’s sole degree-granting body until 1961. Williamson was a young school teacher in the Whanganui district who came to Dunedin to attend the new university. At least one other foundation student came from the North Island, indicating Otago’s status as a national university from the start; Thomas Hutchison also hailed from Whanganui. Hutchison, just 16 years old, was destined for a career in the law and as a magistrate; lawyers and future lawyers were quite a feature among the founding students. Sitting alongside Stout in MacGregor’s mental science classes was 28-year-old William Downie Stewart, the lawyer who had trained Stout; meanwhile, another of Stewart’s law pupils, his future legal partner John Edward Denniston, attended Latin classes. Denniston, who was 26, had been a student at Glasgow University before migrating to New Zealand with his family in 1862; his father was a Southland runholder. Denniston later became a judge.

William Downie Stewart was one of several lawyers or future lawyers among the first students. He was called to the bar in 1867, and this photo was perhaps taken to mark that occasion. Stewart later served in the House of Representatives and Legislative Council. His son, William Downie Stewart junior, was also a well-known lawyer and politician. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, William Downie Stewart papers, MS-0985-057/073, S16-683d.

For several other founding students, the university was a step on the way to a career in the ministry. David Borrie of West Taieri, Charles Connor of Popotunoa, John Ferguson of Tokomairiro and John Steven of Kaitangata all studied at Otago before undertaking specialised theological training to become Presbyterian ministers. Ferguson and Steven were already school teachers, pupil teaching being a common route to ‘improvement’ for pupils who did well at school. Connor was just 15 when he signed on at the university. His father, the Presbyterian minister at Popotunoa (Clinton), wrote to the council to enquire if his son could undertake university education without a good grounding in Greek. The cash-strapped clergyman would, he noted, find it impossible to support his son in Dunedin for another full year at the high school, but could stretch to the shorter university session. Charles was ineligible for the university scholarships offered students for the Presbyterian ministry as he was under 16. Meanwhile, Ferguson was able to fund his studies thanks to his success in a competitive exam for the Knox Church Scholarship, worth £30 a year for three years. Connor managed to win a scholarship in his second year; this one was offered only to second-year students, suggesting it was tailored for him, the only candidate. Ferguson and Connor both later travelled ‘home’ for further study in Scotland, while Borrie and Steven completed their ministerial training locally. Thomas Cuddie was another founding student intent on a career in the ministry; sadly he died (probably of tuberculosis) just a couple of months after classes began.

Charles Connor was one of several future Presbyterian ministers among the founding students. His photograph sat alongside that of Peter Seton Hay in the Hay family album – they lived in the same country district. It is tempting to think these photos date from the time they began at the university, when Peter was about 18 years old and Charles just 15. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, P2010-011/1-025, Album 605, Hay family portraits, S16-683b.

These men were just the sort of people the university’s founders had in mind. They helped boost the ranks of well-educated teachers, lawyers and ministers, making the country less dependent on imported professionals. Most had arrived in the colony as children or young men and they and their parents had aspirations for a good education. Most might be described as middle class, but some were of humbler means. Thomas Cuddie, for instance, was the son of labouring parents with a struggling small farm at Saddle Hill; he was born aboard the Philip Laing, which brought some of the earliest colonial settlers to Otago in 1848. It would have been impossible for this pious but poor family to fund an education further away without substantial help. Some influential people believed the country would have been better to set up scholarships for New Zealanders to obtain a university education overseas rather than founding a local institution so early, but others were concerned about sending their young people far away and beyond the influence of family; furthermore, some of the most talented might not return. In any case, once a local university was a reality, it became the most accessible option.

Ferdinand Faithfull Begg – Ferdie to his family – photographed in the 1880s. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Album 398, p.17, Cargill family portraits, S16-683c.

There is some evidence of a ‘brain drain’ among the founding students. As would remain the case, some of the brightest were attracted to further study or other opportunities in Europe and not all returned. Peter Hay’s professors were keen to send him to Cambridge, notes one biography, but Hay ‘did not concur, having other than mathematical plans in which Cupid played a part’. For others of this migrant generation the ties to Otago and New Zealand were not so strong. Two went on to interesting careers in Britain. Cecil Yates Biss was born in India, where his grandfather was a Baptist missionary. He came to New Zealand in his teens with a brother and worked in various civil service jobs, including for the post office. After studying Latin and Greek at the University of Otago in 1871, Biss headed to Cambridge, where he completed the Natural Sciences Tripos with first class honours in 1875; he then qualified in medicine. He became a respected physician, researcher and lecturer in England, though his career was cut short by illness. He was also well known as a leading member of the Plymouth Brethren, and a colleague recalled that the non-smoking teetotaller was ‘rather given to admonishing his patients in regard to excesses and irregularities in living, in addition to ministering to their immediate ailments’.

Ferdinand Faithfull Begg was one of several businessmen among the founding students. He was the son of a prominent Edinburgh Presbyterian cleric. Begg joined his brother in Dunedin in 1863, acquiring good business skills in a bank and a large land agency. He performed well in the advanced maths class at the university in 1871 and returned to Scotland with his father, who had been out on a visit, the following year. There he became a prominent stockbroker, chairing the Edinburgh Stock Exchange and later the London Chamber of Commerce; he was also a member of parliament. One of Begg’s other claims to fame was to be ‘the first to ride a bicycle on the streets of Dunedin’; in 1871 he imported a ‘boneshaker’, complete with wooden wheels, brass pedals and iron tyres, backbone and handles.

There were no women among the founding students, but several joined classes the following year – I’ll feature the story of the admission of women in the next blog post!

University of Otago founding students – an incomplete list

From newspaper reports of exam passes:

- Begg, Ferdinand Faithfull

- Biss, Cecil Yates

- Borrie, David

- Cameron, J.C. [John Connelly?]

- Connor, Charles

- Denniston, John Edward

- Dick, Robert

- Duncan, James Wilson

- Dunn, John Dove

- Ferguson, John

- Fraser, J.M.

- Hay, Peter Seton

- Hirsch, Gustav

- Hutchison, Thomas

- Lusk, Thomas Hamlin

- Steven, John

- Stewart, William Downie

- Stout, Robert

- Wilding, Richard

- Williamson, Alexander Watt

Named in Williamson’s diary:

- Cuddie, Thomas Alexander Burns

Entered in university cash book paying fees:

- Allan, Alexander George

- Heeles, M.G. [Matthew Gawthorp?]

- Hislop

- Holder, H.R.

- Holmes, G.H. [George Henry?]

- Johnston

- Morrison

- Smith, F.R.

- Taylor, W.

- White, Clement

Wrote to secretary stating their intention to attend classes:

- Adam, Alexander

- Colee, Robert Alexander

- Hill, Walter

- McLeod, Alexander

I’d love to hear of any other 1871 students, or further details of those listed.