Tags

1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, capping, Christchurch, food science, Helensburgh, languages, Maori, medicine, microbiology, physical education, recreation, St Margaret's

This is a plea for help! Today’s post is rather different from previous ones. I’m posting some photographs I’d like to know more about. Some have appeared on the blog previously, while others are new. They’re all interesting images that I’m thinking of including in the University of Otago history book, and it would be great to have more details before they appear in print. Do you recognise any of the people or places or activities, or can you help with missing dates? If so, I’d love to hear from you, either by a comment on this post, or by email or letter (the ‘about’ page has a link to my university staff page with contact details).

I’ve gathered lots of images from archival, personal and departmental collections over the last few years, but I’m still short in some areas. In particular, I’m keen to locate photos relating to activities involving the commerce division/school of business and the humanities division (though I have a good supply of photos for the languages departments). Zoology, maths and psychology are other departments I’d like to find more images for. Where more general images of student life are concerned, I’d love to find a few photos relating to life in student flats and to lodgings and landladies. I have plenty of capping parade photos, but some other photos of student activities would be great. Overall, the 1980s are a bit of a gap in my lists of potential illustrations, so I’m on the lookout especially for anything from that decade, and to a lesser extent the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s. Another major gap is for images relating to the Christchurch, Wellington and Invercargill campuses. If you have any interesting photos you would be willing to lend to the project, please do get in touch!

Now, on with the mystery photos …

1. Gentlemen dining

Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Irvine family papers, MS-4207/006, S16-669a.

These gentlemen, about to indulge in a little fine dining at the Christchurch Club, have connections to the early years of the Christchurch Clinical School (now the University of Otago, Christchurch). Those I have identified so far were either senior Christchurch medical men or Otago administrators and members of the Christchurch Clinical School Council. That council was organised in 1971 and met for the first time in 1972. Max Panckhurst, an Otago chemistry professor who was on the council, died in 1976, so the photo must date from before that, and since it also features Robin Williams, who completed his term as Otago Vice-Chancellor in 1973, it probably comes from the early 1970s. Do you know the exact occasion or year?

The men I have identified are, starting from Max Panckhurst, who is closest to the camera with fair curly hair, and working clockwise: LM Berry, Carl Perkins, George Rolleston, Robin Williams, Leslie Averill, Alan Burdekin (Christchurch Club manager,standing), Bill Adams, LA Bennett, Robin Irvine, unknown, unknown, Pat Cotter (partly obscured), D Horne, Don Beaven, unknown, Fred Shannon, Athol Mann, JL Laurenson. Do you recognise anybody else? Or have I got any of these wrong? Some other potential candidates, who were also on the Clinical School Council, are EA Crothall, DP Girvan, TC Grigg and CF Whitty.

2. Burgers

Were you a Burger? After I published a story about Helensburgh House, a student hall of residence in the former Wakari nurses’ home, I met up with Glenys Roome, who had been its warden. She kindly shared some photos, including these three. Helensburgh House ran from 1984 to 1991 – I’d love to identify which year these were taken, and perhaps some names!

3. The missing singer

Photo courtesy of Michael Shackleton.

All but one of the members of the 1952 sextet in this photo are identified – can you help with the full name of the young man third from left? His first name was John. The lineup was, from left: Linley Ellis, Richard Bush, John ?, Keith Monagan, Michael Shackleton, Brian McMahon. The story of the sextet featured in an earlier post.

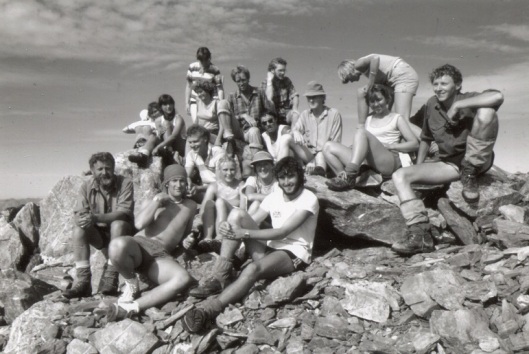

4. On the rocks

Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Otago University Tramping Club records, 96-063/036, S15-592b.

This is one of my favourite photos – it’s already featured on the blog a couple of times and is sure to end up in the book! In the original tramping club album it is identified as being at Mihiwaka, but somebody kindly pointed out when I posted about the tramping club that this is most likely taken from Mount Cargill. Do you recognise this spot? And can you identify any of the 1946 trampers?

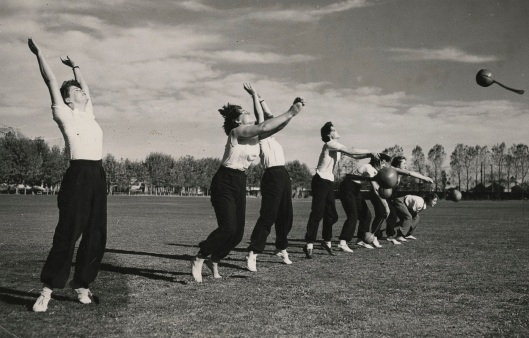

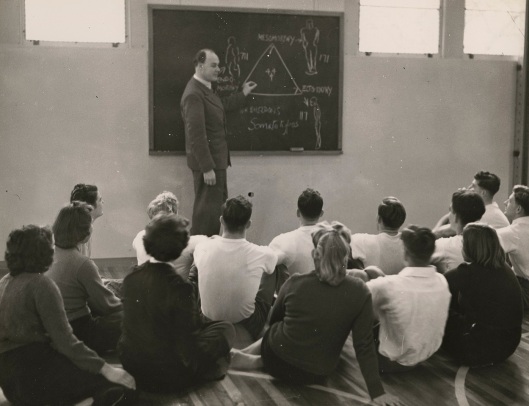

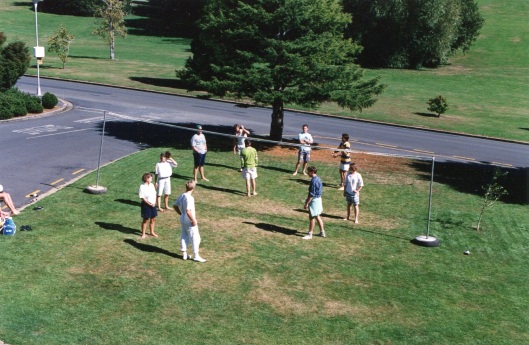

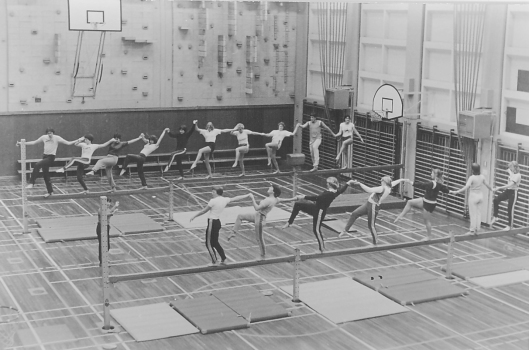

5. Phys-eders

The School of Physical Education, Sport and Exercise Sciences has kindly shared some of their photo collection. The photograph on the beams was taken in the 1970s – were you there, and do you know the exact year? How about the others – any ideas where and when they were taken, or who the people are? I published a post about the early years of the phys ed school in an earlier post, and there are photos on that I’d love to have more information about too, so please take a look!

6. Te Huka Mātauraka

Photo courtesy of the Māori Centre

This photo was taken outside the Māori Centre, Te Huka Mātauraka, in 2002 and featured in a post about the centre. Can you identify anybody?

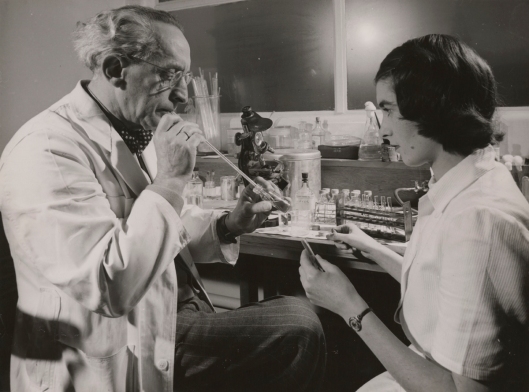

7. Microbiologists

Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Department of Physiology records, r.6681, S16-521c.

This photograph is a good example of the value of this blog. In the original, the man is identified as Franz Bielschowsky, of the cancer research laboratory. When I included it in a story featuring Bielschowsky, people informed me that the man here is actually Leopold Kirschner, a microbiologist working in the Medical Research Council Microbiology Unit. It was probably taken in 1949. Typically for that period, the female assistant is not named – do you know who she is? What, exactly, are they doing? I suspect health and safety procedures have changed since then!

Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, University of Otago Photographic Unit records, MS-4185/042, S15-500d.

Here’s another microbiology-related photo, taken during the first hands-on science camp in 1990 – it featured in an earlier post about hands-on science. Can you identify any of these high school students? I’m curious to know if any of them ended up as University of Otago students!

8. The St Margaret’s ball

Image courtesy of Peter Chin.

This photograph, taken at an early 1960s St Margaret’s ball, featured in a story about Chinese students at Otago. At centre front are Jocelyn Wong and Peter Chin – can you identify anybody else? Exactly which year was it?

9. Picnickers

Image courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: 1/2-166716-F. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22884184

The Latin picnic was a popular event in the early twentieth century. This photo was taken at Whare Flat in 1932 – it featured in an earlier post about writers at the university. People identified so far include Dan Davin, on the far right, with Angus Ross in front of him and Christopher Johnson to Davin’s right. Other students include Frank Hall (back left), Winnie McQuilkan (centre front) and Ida Lawson (in dark jacket behind her). The Classics staff, Prof Thomas Dagger Adams and Mary Turnbull, are at front left. Can you identify anybody else?

10. In the food science lab

I featured these mystery photos quite some time ago on the blog, and people have identified Rachel Noble, a 1980s student, as the woman in the centre of the bottom image. The food scientists tell me these students were in the yellow lab, possibly working on an experimental foods course or the product development course run by Richard Beyer. Can you help with the date, or identify any of the other students?

Images courtesy of the Hocken Collections, from the archives of the Association of Home Science Alumnae of NZ, MS-1516/082, S13-556b (above) and S13-556c (below).

I have quite a few other photograph puzzles, but will save those for future posts!

Update

Thanks very much to those of you who have identified some of the mystery people already – yay! And thanks for the kind offers of further photographs. For those with photographs, here are a few instructions. If they’re already digital, that’s great. If you are scanning them, it would help if you make them high resolution (say 300dpi), preferably in TIFF format, but JPEGs are okay. If they are hard copy, I’m happy to scan them for you if you’re willing to lend them to me – I promise to return them promptly. I can pick up items if you’re in Dunedin, otherwise you can post them to me (it’s probably easiest if you send them to Ali Clarke, c/o Hocken Collections, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9054). Remember if you’re sending images that you need to be willing for them to appear, potentially, in the new university history book (due out 2019) or on this blog! I’ll send you a form to sign granting permission for their use in university publications. Any published photos will be attributed to you; do let me know if there’s a photographer I should clear copyright with as well. Thanks 🙂