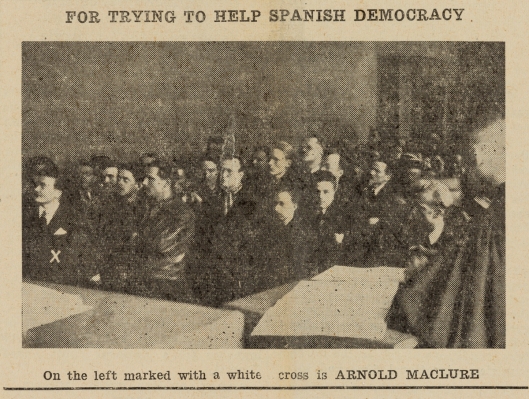

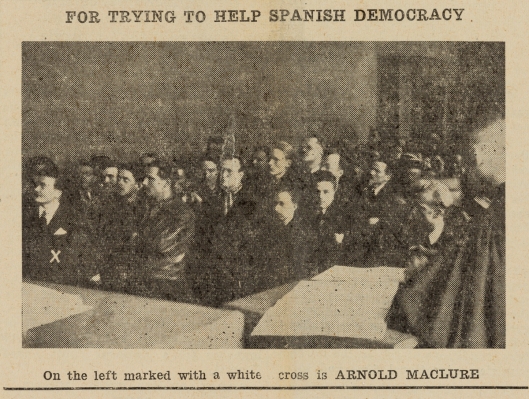

Alexander Maclure (mistakenly named here as Arnold) and other international volunteers arrested while attempting to enter Spain, at an appearance in a French court in 1937. Image from the Workers Weekly, 2 July 1937, courtesy of the Hocken Collections, S16-521d.

I’ve written previously about the university in World War I and World War II, so to mark Anzac Day this year I’m exploring the intriguing and little-known story of an Otago student killed in one of the other conflicts of the 20th century, the Spanish Civil War. Alexander Crocker Maclure was not your average Otago student. For a start, he came from Canada, not a common origin for students at that time. Born in 1912, Alex Maclure grew up in Montreal. After leaving school, where he did well, he headed to remote northern Manitoba, working as a wireless operator at Fort Churchill. He was, it seems, a man of adventure and one keen to escape his roots in Westmount, a wealthy Anglophone enclave of Montreal. His parents loved their oldest son, but had no time for his leftist politics; indeed, his father chaired the council of the Montreal branch of the Royal Empire Society. In 1931 Alex Maclure enrolled at the Otago School of Mines. We can only speculate about why he came here when he could have attended one of Canada’s mining schools. The Otago school had a distinguished international reputation, so perhaps that was the drawcard; perhaps he wanted also to explore a new country.

There were only around 1100 students at Otago when Maclure arrived, and he quickly earned the reputation of being the most politically radical person on campus. That wasn’t an especially big challenge: a study by Sharon Dooley of Otago students in the depression concluded that most were ‘conservative members of the middle class’, preoccupied with completing their qualifications. There were a few, like future history professor Angus Ross, who were shocked by the poverty they witnessed in those difficult times and took an active interest in politics as a result, but Maclure was unusual in being a committed member of the Communist Party (it expelled him more than once for unorthodox views). Maclure was a driving force behind the formation of the first formal left-wing groups on campus. The Public Questions Union, first affiliated to OUSA in 1932, organised regular discussions and mock parliaments; it also served as a ‘front’ for the Independent Radical Club, ‘an influential cell’ of more radical students, with about 30 members by 1935.

Maclure was heavily committed to his political beliefs. He was always up for a discussion and a very good speaker, though his views shocked many. He started out living at the Dunedin YMCA and later lived in digs in Cumberland and Hyde streets. His university enrolment card for 1935 gave his address as ‘no fixed abode’; that may have been when friends recalled him living in a deserted house, unable to afford heating or food. He had little choice but to turn to his parents for financial support. Writer Dan Davin, a student contemporary, later wrote a vivid portrait of Maclure (disguised as McGregor) in his short story ‘The Hydra’, published in The Gorse Blooms Pale in 1947. It revealed the radical as an extremist, who always ‘seemed too vehement, slightly absurd’; other students threw him in the Leith when he advertised the first meeting of the Radical Club. But Davin also expressed some sympathy with Maclure’s views on food riots by the unemployed, and felt uncomfortable at his conviction and fine for scrawling political slogans on Dunedin footpaths. Maclure wrote about politics wherever he could, including in student publications Critic and the Otago University Review. Meanwhile, he slogged his way through the mining course, completing some of the practical component in the West Coast mines. He took a year off his course in 1933 and it is unclear what he did then; perhaps he simply got a job to fund his later studies. He completed his final course work at the school of mines in 1936; he didn’t receive his diploma, but that was only because he had yet to complete the required thesis about his practical work, often submitted by students a year or two after they left the mining school.

Maclure now had other priorities. Like other political junkies he developed a keen interest in events in Spain, where in 1931 a coalition left-right government took over from the previous deeply conservative dictatorship and monarch, and after the 1936 election a coalition leftist government – the Popular Front – won power. Later that year the right-wing military began an uprising, led by General Francisco Franco, and a brutal civil war broke out in earnest; the war was eventually won by Franco in 1939. The fight was confined to Spain, but it had much broader significance as a battle between the extremes of left and right in a region where fascism was on the rise. Hitler and Mussolini committed resources, including troops, to Franco’s cause and, in the absence of any effective intervention from other countries, leftists around the world recruited volunteers to support the republican government’s battle against the right. The International Brigades, as they were known, eventually included around 40,000 volunteers from 50 countries. Soon after the war broke out Alex Maclure helped set up the General Spanish Aid Committee, later absorbed into the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, which became this country’s major relief organisation for the war.

But Maclure wanted to do more than raise funds. Early in 1937 he returned briefly to Canada, where he joined a group of Canadian and American volunteers heading to Spain. He intended to get involved in the blood transfusion unit, but because of his record as a crack marksman (he won prizes for his shooting ability at school) he was posted to a fighting unit of the MacKenzie-Papineau Battalion. The first challenge was to gain entry into Spain, as France closed its border in February 1937. Maclure and some of his companions were captured by French authorities while travelling up the Mediterranean, hidden in the hold of a fishing vessel; together with several others, picked up by border patrols in the Pyrenees; they spent 20 days in a French prison for evading a non-intervention agreement, which supposedly banned all foreign powers from intervening in Spain. The Workers Weekly, the New Zealand communist paper, published a letter from Maclure in jail, as did the Grey River Argus. The prisoners were in high spirits, and received lots of support from French locals. They finally made their way into Spain some weeks later, crossing by foot in darkness over mountain trails.

Maclure’s movements in Spain remain unclear, but he became sergeant in charge of one of the American Division’s machine guns and was reported wounded and missing in August 1937; he died a couple of months later, probably in battle at Fuentes de Ebro, in the Zaragoza (Saragossa) province of northern Spain. News of Maclure’s death reached Dunedin in December 1937; the Workers Weekly proclaimed the heroism of a comrade ‘killed in action defending, with his comrades in the International Brigade, freedom and world peace against the Fascist invaders’. He ‘demonstrated that New Zealand can point to men to whom freedom means more than life itself’. An obituary in the first issue of Critic for 1938 recalled Maclure’s years as an Otago student, noting his ‘considerable’ intellect and his whole-hearted promotion of his Communist beliefs. ‘His enthusiasm, his sincerity, his moral fearlessness earned him the regard of all who respect such qualities’. Critic did not, naturally enough, demonstrate such approval of Maclure’s politics as the Workers Weekly, commenting that ‘there are many who heartily deplore the theories for which Maclure fought’. It did, however, acclaim his sincerity: ‘to whatever creed we cling we can not but feel admiration for the rare and fine qualities in Maclure’s character, qualities that are revealed by his giving up his life for his ideals’.

Maclure was, to the best of my knowledge, the only Otago student or graduate to serve as a frontline soldier in the Spanish Civil War, but a couple of others did play significant roles in journalism and medicine. Geoffrey Cox completed an MA in history at Otago before heading to Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar in 1932. He stayed on in England, beginning an acclaimed career in journalism as a junior reporter for the News Chronicle. In the early months of the Spanish Civil War, Cox became the paper’s correspondent in Madrid. The original correspondent had been captured, and Cox suggested he was sent because the paper saw him as junior enough to be expendable. His reports from the Spanish capital, then heavily besieged by Franco’s forces, became one of the few sources of information to the outside world. His vividly written eye-witness account of five weeks in Madrid was published in the book Defence of Madrid the following year. His reputation as a correspondent grew as he reported for the Daily Express from Vienna and Paris in the years leading up to World War II, covering the Anschluss and Munich crisis and the invasion of Poland, then the war in Finland and German invasion of the low countries. After the fall of France he signed on with the New Zealand Division and served with distinction. When the war ended he returned to his career as an English newspaper journalist, later becoming a pioneer of television journalism.

Geoffrey Cox, photographed by S.P. Andrew in 1932. Image courtesy of the Alexander Turnbull Library, reference 1/2-C-22830. Alexander Turnbull Library

Douglas Jolly was another Otago graduate who published a book based on his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, but it had a very different purpose: to equip surgeons for battle. Jolly graduated in medicine in 1930. During his university years, and later, he was heavily involved in the Student Christian Movement, becoming a convinced Christian socialist. When the war broke out in Spain he was in England, close to completing his specialist qualifications as a surgeon. As the republicans lost most of their military medical services with the army rebellion and the Red Cross refused to intervene in an internal conflict, there was a call for international volunteers to support the leftist cause. Jolly immediately abandoned his studies, arriving in Spain in November 1936 with the first contingent of British medics. He was assigned to the XI International Brigade, for whom he formed a 50-bed mobile surgical unit. He gave two years of almost continuous service as a frontline surgeon, only departing when all international volunteers were withdrawn from Spain. He proved an excellent surgeon, ‘courageous and totally reliable’, much respected by all with whom he served. His patients included civilians injured in air raids alongside frontline soldiers, and the settings for the ever-mobile field unit ranged from the basement of a shell-ruined flour mill to railway tunnels and a cave. After the war he campaigned on behalf of post-war refugees, including during a return visit to New Zealand in 1939. When World War II broke out he returned to England and wrote the medical manual Field Surgery in Total War, published in October 1940 to glowing reviews. His advice on abdominal surgery saved many lives, and his systems for dealing with multiple injured patients became the basis for surgical units in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. Doug Jolly also signed on with the Royal Army Medical Corps, serving as a surgeon in North Africa and Italy. His long service on the battlefields of two wars eventually caught up with Jolly; after World War II he lost his enthusiasm and confidence for surgery, spending the rest of his career as medical officer at Queen Mary’s Hospital for amputees in London.

Marianne Bielschowsky in April 1939. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Bielschowsky papers, MS-1493/036, S16-521d.

The involvement of two later Otago staff members, Franz and Marianne Bielschowsky, in the Spanish Civil War was less intentional than that of the three Otago-educated people already mentioned. They were already living in Spain when war broke out. Franz Bielschowsky, son of distinguished German neurologist Max Bielschowsky, undertook his medical training in a succession of German universities before completing an MD at Berlin and embarking on a career in medical research in Dusseldorf. Early in 1933 he was dismissed from his job because of his Jewish parentage and fled to Amsterdam. In 1934 he relocated to Madrid, where he became a lecturer in the medical faculty; in the following year he was appointed director of the biochemistry department of the new Institute for Experimental Medicine at the Central University of Madrid. Marianne Angermann, a German biochemist who had worked with Franz Bielschowsky in Dusseldorf, joined him at the Institute in Madrid late in 1935; they were to marry in 1937. Angermann and Bielschowsky refused offers to leave Spain when the civil war began; they did not feel vulnerable and respected the support they saw for the republican government. But as the siege of Madrid lengthened, their research work became impossible. Franz joined the republican medical service and worked at a military hospital in Madrid. The Bielschowskys remained in Madrid after the withdrawal of international medical staff in 1938, but fled Spain early in 1939, as Franco’s forces prepared to enter the capital. They were now refugees for a second time, and as war took over Europe they ended up in England. They both obtained work at the University of Sheffield, where Franz’s research took a new direction, investigating the role of hormones in the development of cancers. In 1948 the Bielschowskys arrived in Otago, where Franz had been appointed director of the cancer research laboratory. Like his work in Sheffield it was sponsored by the British Empire Cancer Campaign Society. Franz continued a productive research career at Otago for 17 years, until his sudden death in 1965. Marianne, who worked alongside him, continued her work until her own death in 1977. She was especially known for her development of various special strains of mice, used worldwide for medical research.

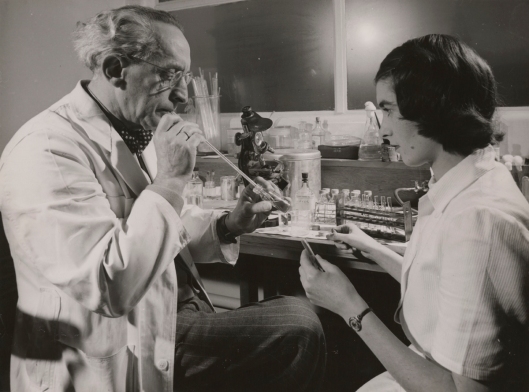

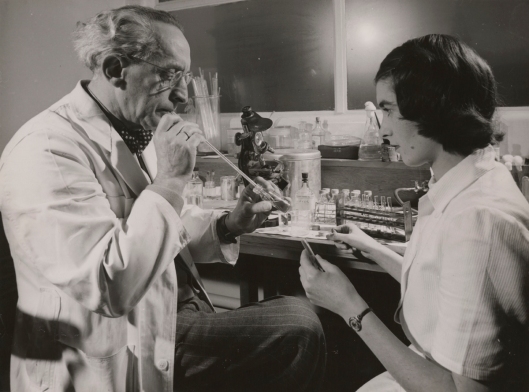

Franz Bielschowsky in 1949, when he was Director of Cancer Research at the University of Otago. Image courtesy of the Hocken Collections, Physiology Department records, r.6681, S16-521c. (I would be delighted to hear from anybody who can identify the woman in this photo).

The Spanish Civil War of the 1930s might be dismissed as foreign by many New Zealanders, but its dramatic progress caught up several people from these distant shores. The involvement of people connected with Otago reflected the international influences – and standing – of this university. There were an international student from Canada whose politics drove him to his death in a fight against fascism, and two New Zealanders – a Cromwell-born doctor and a Palmerston North-born journalist – who took the skills developed at Otago and further honed in England to make their own contributions during that brutal war. Last, but by no means least, came the cultured German scientists whose fortunes became caught up in that war; it was one of the events which led them to eventually settle and make an important contribution in this more peaceful corner of the world.

I am grateful to Wellington historians Simon Nathan and Mark Derby for sharing information about Alexander Maclure. I highly recommend to anybody interested in learning more the book edited by Mark Derby, Kiwi Compañeros: New Zealand and the Spanish Civil War. Mark tells me discussions are underway about a possible memorial to Doug Jolly in his home town, Cromwell.

An update (18 July 2016) – somebody who knew the Bielschowskys has kindly been in touch to alert me that the photo labelled as being of Franz is not actually him! She suggests it may be of Leopold Kirschner. If you recognise this gentleman, I’d love to hear from you.

A further update (20 July 2016) – a couple more people have confirmed that the man in the laboratory photograph is not Franz Bielschowsky, but Leopold (‘Poldi’) Kirschner. Kirschner was a microbiologist and worked in the Medical Research Council’s Microbiology Research Unit. He was another of Europe’s Jewish diaspora.Originally from Austria, he did important work on leptospirosis in Indonesia, but was interned there during the war. He continued the work on leptospirosis at Otago. My sincere thanks to those who helped correct the photo identification. The identity of the woman in the photo remains a mystery – suggestions are welcome!